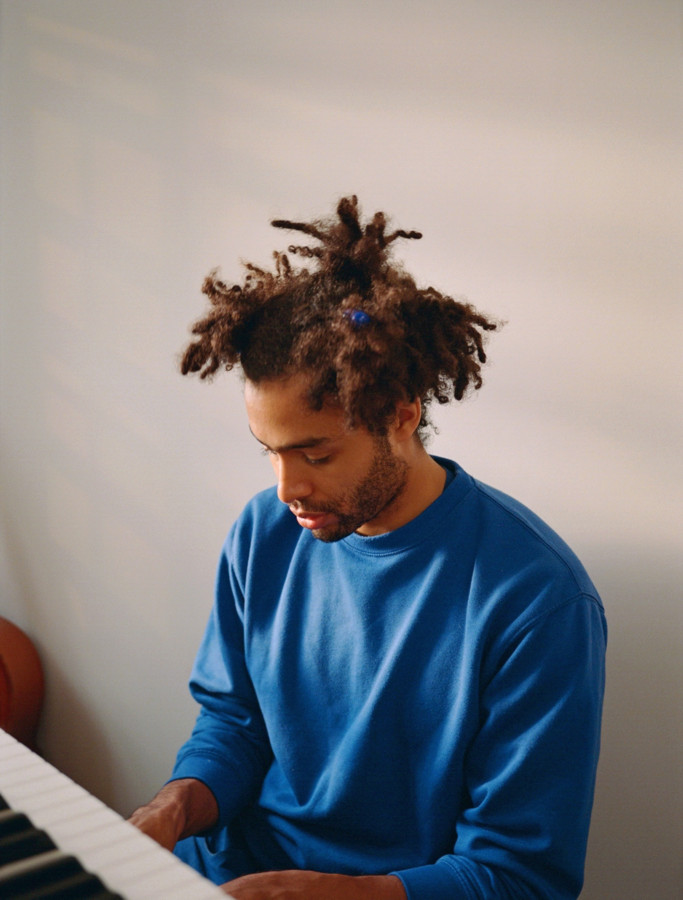

The last time Duval Timothy released an album of songs, on 2018’s 2 Sim, he was surrounded by voices. They were intimate and eloquent and everywhere. Sourced from personal voice notes and field recordings that he pulled from his WhatsApp and captured with his digital audio recorder, they belonged to friends and family in Sierra Leone where Timothy’s father migrated from and where Timothy, born and raised in South London, has been returning to— making films, making music, painting, and learning to weave. They talked of passports, rainstorms, and beaches, and ruminate— over acoustic piano, layered electronics, and the occasional avalanche of beats— on being West African in London and being Afro-British in West Africa, on living a life with two SIM cards, a diaspora life of proximity and distance and family mirrors that don’t always reflect neatly back.

On Help, the voices are fewer and more inscrutable. They are usually allowed only a word or a phrase. They are clipped and panned, time-stretched, and pitched up and down. They are treated like discrete units of matter, strategically drawn in and let go. There are only two voices that are given full sentences. The first, which comes after Ibiye Camp’s sampled utterance of the word “slave” is twisted into a series of melodic looped knots, is a YouTube audio rip of Pharrell Williams critiquing record companies who play Master and force musicians into the role of contractually enchained property.

The second belongs to the late painter Ellsworth Kelly. After a minute of sparse solo piano on “Look,” Timothy plays a recording:

I don’t like decoration—it’s like bad painting. Because, to me, a painting really has to really mean something. To me, I mean. It’s hard to say what it means except what you feel and what you can do with it by looking and investigating. I think Diane Arbus said, “If you investigate enough, everything becomes abstract,” and I like that, so I use it.

And then after another minute of piano, effects, and the distant honk of car horns, more Kelly:

I remember coming down the stairs and seeing this yellow pound of butter, I went to it and stepped on it... and stepped on it and it was all flat. I don’t like bulk. Thickness. Three dimensions. My paintings have always been planar. And so my mother came out and said, “Look what you’ve done... you’ve made art!

The statements of Williams and Kelly are among the few transparent pillars holding up Help’s otherwise opaque and shimmering sky. Timothy’s compositions grapple with historical legacies of enslavement and ownership across the maps of Black music. They also, simultaneously, pursue an intensive aesthetic investigation that borrows from visual traditions of abstract art, conceptualism, and the deep resonant flatness of color field painting (influences that have all left their mark on Timothy’s films, paintings, and textile work as well.) In addition to a figure like Kelly, Help also further connects Timothy’s work to that of the U.S. artist Jennie C. Jones, whose paintings and sound objects—and whose own theory of “listening as a conceptual practice”— urges a reconsideration of abstract art as a form of Black avant-gardism (and vice-versa).

If 2 Sim and 2017’s Sen Am bent abstraction toward audio documentary, Help bends back toward the edges of non-referentiality. The achievement of the album—which is anchored in the warmth and delicacy of Timothy’s ever-present acoustic piano— is that so few elements are asked to add up to anything fixed or easily digestible. Timothy allows them to bubble and linger and then dissipate into the air without leaving a trace. Carefully laced with blurred keys, anonymous whoops, far-away clangs, and slick guitar flutters, the songs abide by invisible geometries. As he does in his textile work, Timothy carries colors (a version of the name his clothing line once carried) across these minimalist sonic sketches that blur the edges of tone and hue. He called his 2016 album Brown Loop, but the loops on Help listen across palettes, gradations, and intensities.

In his landmark study, Interaction of Color, Josef Albers famously wrote that the longer you look at a color the more you can see its “after-images.” Timothy makes music that if you listen closely enough, long enough, you can hear something like “after-sounds.” These are not the “ghost notes” between beats that Timothy sampled legendary drummer Bernard Purdue talking about back on his 2012 debut

Dukobanti. Instead these are the notes and tones that appear only after all the other notes and tones leave the ear— sounding after sound. Albers, of course, also painted cover art for albums like Provocative Percussion and Persuasive Percussion Land III, and late in his career became interested in translating fugues and rhythms into the visual language of paintings. I think of Timothy working the other way, translating visual color into the language of sound and music.

There are more conventional ways to talk about this album. Vegyn handles percussion and co-production, Twin Shadow, Dave Okumu and Melanie Faye contribute guitars, Kwes sits in on an Op-1, and Lil Silva co-writes, co-produces and lends vocals to the languid slur of “Fall Again.” As on previous albums, Timothy’s family show up as well, with his brother on trumpet and his sister offering an Afro-pessimist koan on “TDAGB” (Things don’t always get better). The whole thing is ably produced and corralled by Rodaidh McDonald who knows a thing or two about form and un-form from his work with both Adele and King Krule.

But that kind of talk goes against Help’s grain. Are these even songs? I’ve called them sketches, but maybe they are more like shapely soundscapes, or musical case study houses where ideas flash with intense melodic light, and then warp into a radiant darkness. Is that darkness a form of blackness? A figure of it? A re-coding of it? Help continues Timothy’s penchant for abstraction while still wanting to engage with histories of Black diaspora and migration between England and West Africa— a version of what curator Adrienne Edwards once famously called “blackness in abstraction.”

Timothy similarly refuses to choose between one or the other, colorist abstraction or colorist politics. Instead he sits down at his piano, and carries them both. He floats. He listens for the space between distance and proximity, between the repetition of the word slave and its eventual unintelligibility. He settles into the planar beauty of the between and starts to dream.